Western vs. Eastern Style Brewing

How do you brew tea?

How to Brew Tea

Western Tea Service

Western or English-style tea brewing is very popular in Europe and the United States and involves brewing a small amount of leaf relative to the amount of water for 2-5 minutes. You can brew tea in this manner in a tea pot or directly in your mug or cup using a tea infuser.

Western Brewing

How to Brew White Tea

For Silver Needle teas (comprised entirely of downy buds), we recommend brewing 5 grams of white tea buds in 16 ounces of 175° - 185° F water for 5-7 minutes. For bud and leaf white teas like Bai Mu Dan Wang, we recommend brewing 5 grams of tea in 16 ounces of 185° F water for 3 minutes.

Western Brewing

How to Brew Green Tea

We recommend brewing 5 grams of green tea in 16 ounces of 160° - 185° F water for 2 minutes. Japanese green teas such as Sencha will typically benefit from brewing with water on the cooler end of this spectrum (~160-165° F).

Western Brewing

How to Brew Oolong Tea

Most oolongs benefit from brewing 5 grams of oolong tea in 16 ounces of 195° F water for 3 minutes. If you are brewing a rolled oolong, we recommend a brief rinse of your leaves at the same temperature before brewing. Don't forget to save your leaves, as many oolongs resteep 3-5 times in a Western-style pot.

Western Brewing

How to Brew Black Tea

We recommend brewing 5 grams of black tea to 16 ounces of 205° F water for 3-5 minutes. Fans of particularly robust black tea (esp. with a splash of milk) may want to brew 8 grams for 5 mintues.

Western Brewing

How to Brew Aged Tea

Aged teas fall into two categories, raw and ripe. For raw (sheng) aged teas, we recommend a brewing temperature of 195° F. For ripe (shou) aged teas, we recommend a brewing temperature of 205° F. Both types of aged tea should be brewed at a ratio of 5 grams to 16 ounces of water and may benefit from a rinse. Don't forget to save your leaves, as these teas are particularly suited to re-steeping!

Western Brewing

How to Brew Scented Teas

Most scented teas will be best brewed like their base tea. We recommend using a ratio of 5 grams of tea to 16 ounces of water. Some scented teas that are meant to be particularly robust may benefit from using 8 grams of tea, longer steep times, or slightly hotter water.

Western Brewing

How to Brew Herbal Teas

Herbal Tisanes are some of the easiest teas to brew. Brew 5 grams of your favorite herbal infusion in 16 ounces of boiling water for 3-5 minutes and enjoy! Remember: the longer you steep, the more benefit you will extract from your medicinal herbals!

How to Brew Tea

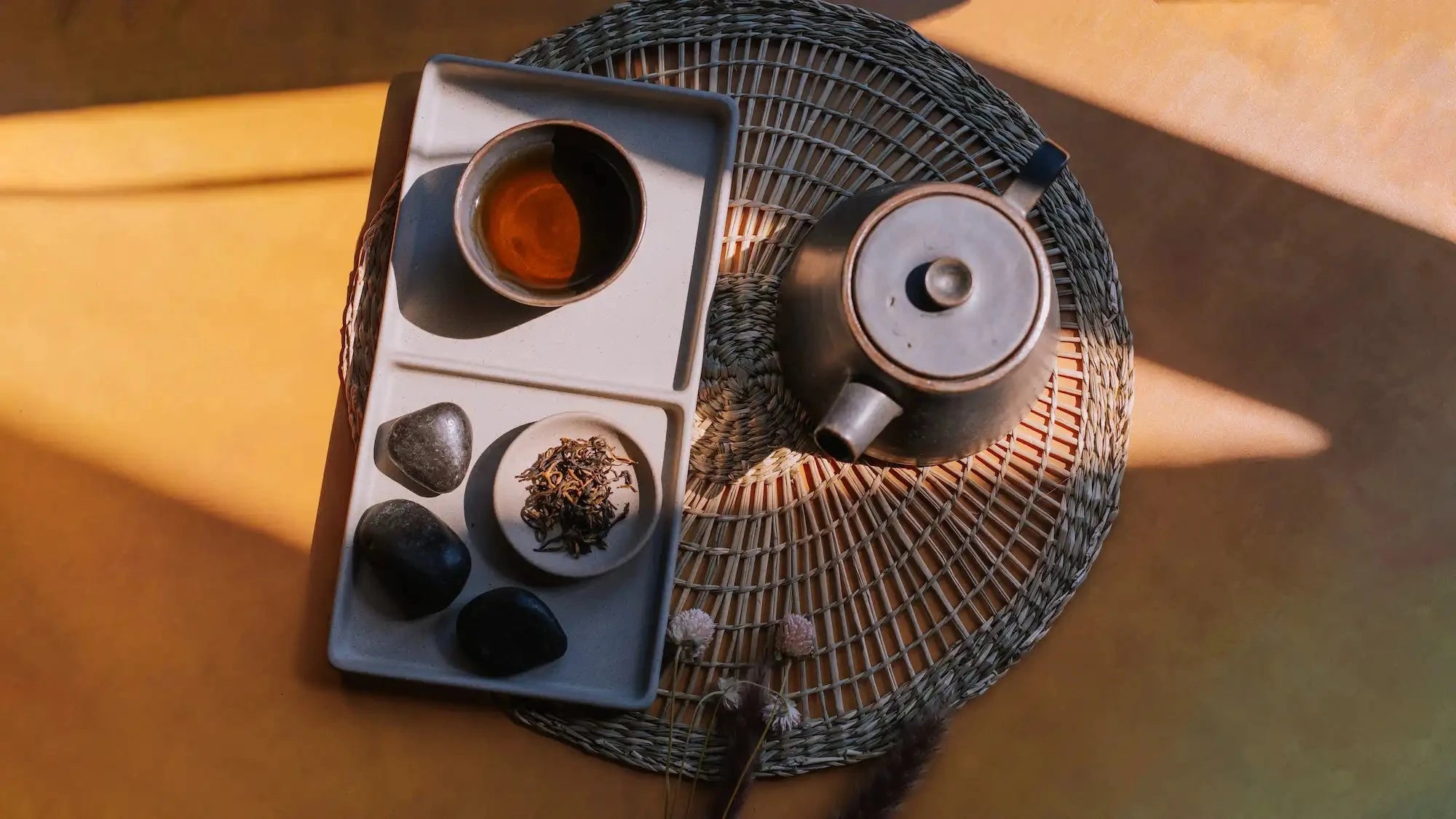

Traditional Brewing: Gongfu Tea Service

Eastern Brewing

How to Brew in a Chinese Gaiwan or Yixing Pot

Brewing in a gaiwan or small Chinese teapot is one of our favorite methods. Each steep is quick and the method is perfect for lingering over multiple resteeps. After preheating your teaware, simply fill your gaiwan or small teapot 1/3 full with leaves (slightly less for rolled oolongs) and cover with the appropriate temperature water. Steep 20-60 seconds (20-30 for green teas and light oolongs, 45-60 seconds for black and aged teas). Resteep many times at decreasing time intervals to enjoy the full potential of your leaves.

Eastern Brewing

How to Brew in a Japanese Kyusu

Prewarm your kyusu with 145° - 175° F water and discard. For a 260ml kyusu, add 7 grams of Japanese green tea. Cover with 145° - 175° F water and steep for 15-30 seconds. Resteep at decreasing time intervals.

SpecialTEA Brewing

How to Make Chai Tea Concentrate

Yield: 2 quarts chai concentrate

For the Concentrate:

Heat 2.5 quarts of water in a saucepan with 30 grams of loose leaf chai (~4 tea scoops) and bring to a boil. Once boiling, reduce heat to low and simmer for 60-90 minutes. Cool your concentrate, strain, and store in the refrigerator for up to 3 weeks, heating portions to serve. Hint: we put our loose leaf chai in nut milk bags when making concentrate to make the tea easy to strain.

Making a Chai Latte:

Compose your chai latte using a ratio of 2/3 chai concentrate and 1/3 frothed milk. We recommend using Cinnamon Infused Honey to sweeten your chai.

SpecialTEA Brewing

How to Make Cold Brew Iced Tea

How to Hot Brew Iced Tea

Shop Iced Teaware

$ 10.00

$ 29.00